When I was a little girl, my mom would hold me close and say, “What’s the promise?” I’d smile with both annoyance and appreciation as I dutifully repeated my lines, “I’m pretty. I’m smart. And I’m nice. I won’t forget it. I promise.” I’d wriggle free of her grip to get back to whatever I was doing—using the couch as a balance beam or walking through the house on my hands.

It wasn’t until 7th grade that I ever thought of myself as anything other than those three things—pretty, smart, and nice. I thought of everyone that way.

“You have a giant, ugly vein that pops out of your forehead, and you look like a boy,” a classmate scoffed at me as I passed by her in the cafeteria just days after my 12th birthday. I had thought we were friends, and I remember the heavy weight of her words as though it were yesterday. I went into the girl’s bathroom and examined my forehead. I didn’t really see a vein. I furrowed, and raised my brows—repeated. Nothing. Now I understand that I couldn’t see the vein, because I wasn’t smiling in the mirror that day, and for this reason, I now appreciate it’s unsuspecting appearance.

I took a big step back from the mirror, angling to get more of my body in its view. Stuck somewhere between puberty and womanhood, it occurred to me that my hips were indeed “too” narrow, my shoulders “too” broad. I didn’t have the curves I saw on the magazine covers. My heart sank. It was the first time I longed for that…and by that I mean something other than what I was. And it certainly wasn’t the last time I’d feel like this.

I got into my mom’s gray Volvo after school and the tears spilled over. “Danielle told me I had a vein in my forehead and no one likes me,” I gasped for air between sobs. “And I don’t know why she is being so mean. And, I mean, um, I didn’t even, um, do anything to her.”

My mom, being the mama bear she is, said with finality, “Screw her. She’s just jealous.” I held tight to those words, wanting to believe that jealousy was her motive, and that I was in fact still pretty. After all, it was number one on my list of promises I was sworn to keep.

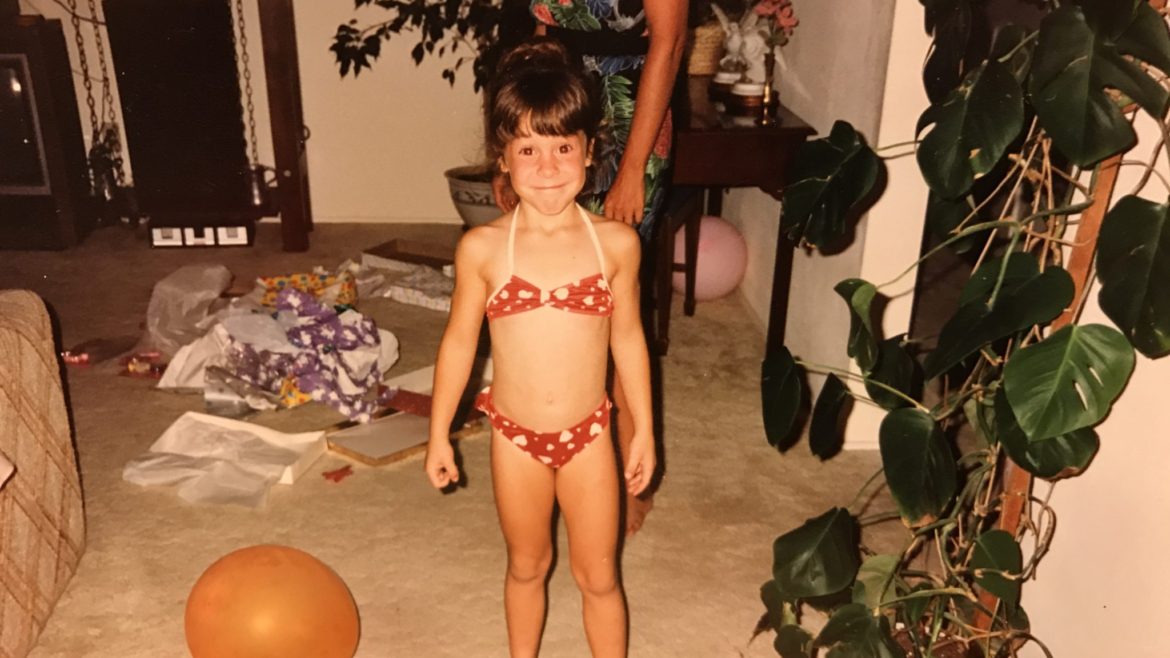

I was a gymnast as a young girl, and muscular like the sport commands. A tomboy at heart, I loved to climb, never sat still, and I spent my days outside on my bike, playing basketball, or skateboarding. I was active—always. I had powerful thighs, narrow hips, and a bust that never grew quite as big as I prayed for after that day in the cafeteria. (Yes, I used prayers to ask for bigger boobs. Jokes on me. They shrunk two sizes after breastfeeding). I was strong. But strong, I’d learn, is not the female body ideal.

In high school, the guys poked fun at my muscular arms, asking if I could beat them up. “We better watch out,” they’d chuckle and exchange high-fives. I’d laugh it off, one hand on my hip as I yelled back that I most certainly could, and they should be scared. I was never really sure if it was callousness or flirtation on their part. At the time, I hoped it was the latter.

In my mid-20s, a brand new mother, I was invited to a friend of a friend’s Crossfit group in their garage gym. As I walked up the dusty driveway, my new baby in tow, I saw the home owner’s thick thighs and muscular arms. Yes, these were my people. And I was right. It was a group of strong individuals, and not simply in the physical sense.

Crossfit and motherhood coincided for me in a way that I can only imagine was more than a synchronistic stroke of fate. A new mother with an unfaithful spouse and impending divorce, I felt uncertain of so much. But I felt at home on the pull-up bar, and even more at home taking breaks to nurse and comfort my son, and garner the support of friends who are now family. Motherhood and my new found sport brought me away from the confines of what I was supposed to be and took me back to who I wish I’d known I was all along—a strong, capable woman.

The bounds of love I felt for my son powered me to love myself deeper. For the first time in my life, I felt strong in every sense. I wasn’t looking for a thigh-gap, or an empty compliment from some guy, but for a 300 pound deadlift. I didn’t give two shits that my arms were muscular. They were there to hold my son as I rocked him to sleep. I didn’t care that my back was broad, because it was the perfect amount of muscle to lift my son high in the air above me and watch as his face smiled down at mine, drool spilling from his bottom lip. I didn’t care that my hips were narrow. They were wide enough to carry a growing life and bring a miraculous soul into this world. And my small breasts, well, they were the perfect size to nourish my son. My body proved itself epic once again when those same narrow hips birthed full-term twin boys a five years later.

I’m not sure what drives people to comment on a woman’s body. Insecurities of their own, perhaps. “You’re too skinny, too fat, too thick, too broad, too bulky, too frail, too muscular, too old, too young, too what-the-fuck-ever,” they’ll say. I’m in my mid-30s now, and people still feel it is their place to comment on my body. They ask if I can beat up my husband. Is my husband scared of me? Do I lift buses or something? Will I get that bulky if I lift weights? It’s always said in jest. I know there’s a dose of judgment behind it though, but what they don’t know is that not only can I lift buses, but I can move mountains. I’m a mother.

My mom succeeded with her intent in raising a strong and confident woman, and for that I’m appreciative. I only wish our society didn’t put so much value on being “pretty” in the first place. But it does. So here’s the deal. Someone will always have something to say about your body, my body, and her body. So that leaves only one option—how we choose to internalize it. We must change how we define pretty. So let’s be pretty amazing. Pretty talented. Pretty creative. Pretty innovative. Pretty driven. Pretty bad-ass. And most importantly, pretty fed up with being asked to conform to one female ideal.

I never got the chance to have a daughter. I’m a mom of three boys, and more than likely done having kids, but here is the promise I’d ask her to keep. When I’d say, “What’s the promise?” She’d repeat her lines with that same annoyance and appreciation I displayed. Only she’d say, “I’m capable. I’m kind. I’m me, Mom.”